Witchcraft in Medieval Europe

Witchcraft has a long and varied history. In this article, we focus in on the history of witchcraft in Europe during the medieval period and into the Renaissance. Even within this narrower focus, there is a lot involved with witchcraft and the practicing of magic in Europe to cover. This article splits the investigation of European witchcraft into two sections with the end of the 14th century as a turning point. We will also take a quick look at the medieval origins of some of the modern images of witches, more specifically, their hats and wands.

Prior to the Late 14th Century

Before the end of the 14th century, the attitude towards magic and witchcraft was very different from the 15th century. In this section of medieval European history, the acceptance of witchcraft was relatively widespread. People considered magic to be a part of everyday life. Much of magic in the medieval world up to this point centered around superstitions. Lucky amulets were common. For many medieval people, magic served as a way to try to influence the world around them in a way that was accessible to them. A lot of the medieval world was out of people’s control and thus magic could have served as a way to try to change that. This could range from influencing the weather and crops to avoiding misfortune.

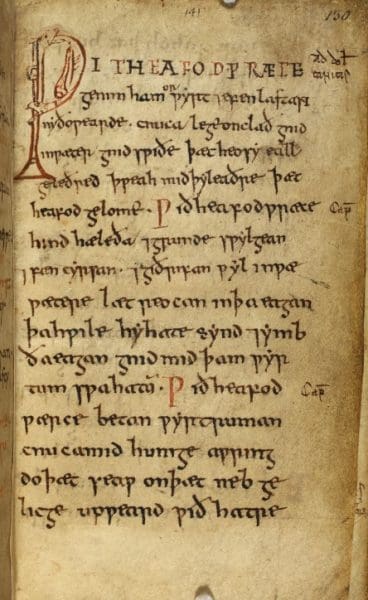

A large portion of medieval magic focused on healing people. In fact, the major portion of the knowledge of Anglo-Saxon magic comes from the surviving medical texts of the period. A late 10th or early 11th century manuscript called Lacnunga, is a great example of this. It is a collection of medieval recipes, charms, and invocations. It is mostly in Old English with parts in Latin and Old Irish. Its charms focus on healing specific injuries or issues.

Magic and the Church

In contrast to later centuries, medieval people at this time didn’t consider the idea of magic to be contradictory to church teachings. In fact, invocations of God or the saints was common or possible. For example, metrical charms were poetic sayings or recitations to help with various issues, including the loss of cattle. One such metrical charm for unfruitful lands, describes asking for the four Evangelists in addition to reciting the Our Father. While part of this charm consists of typical prayers still in use today, there are other parts that involve non-typical superstition.

Late 14th-16th Century

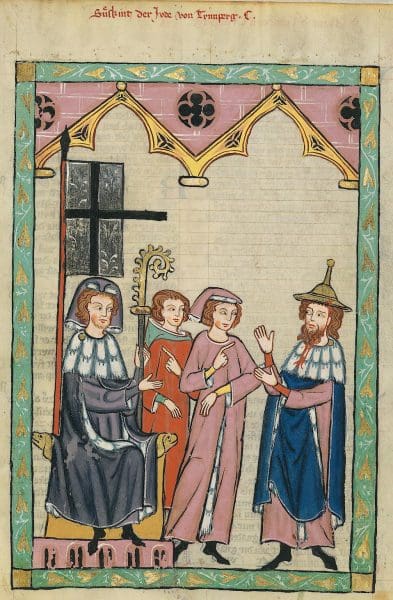

With the turn of the 14th into the 15th century, attitudes towards magic changed. There had been issues with malignant magic prior to this. However, the negative views of magic spread to most types of magic. A case in 1390 focused on the trial of someone accused of soothsaying, aka divination, and false accusations. The false accusations in question were partly focused on the defendant John Berkyng. Allegedly, he accused a sergeant of the Duke of York for theft. While this case illustrates the legal prosecution of witchcraft in medieval Europe, it also indicates the possibility of antisemitism being a contributing factor to the accusations. The first sentence in the record specifically mentions that the defendant was a Jew. Christian judges and countries during the late medieval period and early Renaissance would make connections between Jews and the practice of magic.

Malleus Maleficarum and Heinrich Kramer

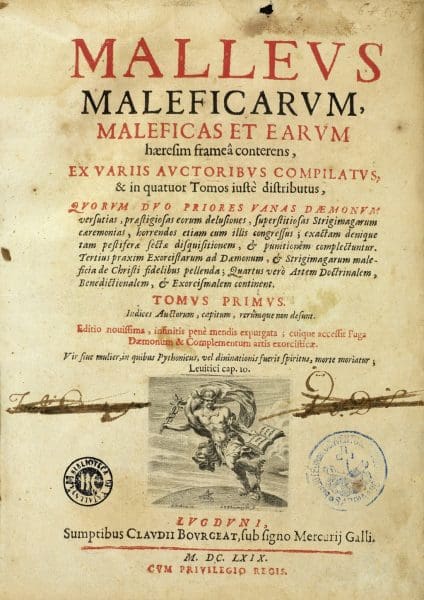

The prosecution of magic really took off at the end of the 15th century. This was due in part to the publishing in 1487 of Malleus Maleficarum, also called the Hammer of Witches, and its main author Heinrich Kramer. Heinrich Kramer was a German inquisitor who wrote the book after being expelled from Innsbruck under shadowy circumstances with possible political motives.

His book became the best-known treatise on witchcraft as well as the best compendium of 15th century literature on demonology. This book became popular enough to be turned into 28 editions between 1486 and 1600. Also, it would be a driving force in the witch hunts of Europe. It called for severe measures against magic and witches. This is in contrast to previous works such as the Sworn Book of Honorius and the Key of Solomon.

While the original publishing date for Honorius is uncertain, the earliest confirmed date stems from the 14th century. This is one of the oldest medieval grimoires and discusses conjuring and commanding demons, angel powers and seals, as well as other pieces of magical knowledge. The Key of Solomon was a 14th or 15th century Italian work that continues the idea of demons. Again, there is a part of this book that focuses on the invocation of God, which follows the harmony with religious teachings mentioned earlier.

Legal Prosecution of Witches

The Hammer of Witches comes in direct contrast with its suggestions for the prosecution of witches. These suggestions include burning them as an extension of the common practice to burn heretics at the time. Condemning witches to death became law in some countries by the 16th century. For example, the English Parliament in 1542 passed the Act Against Witchcraft and Conjurations. This law was repealed in 1547, and then restored by another act in 1562.

History of Wands and Pointed Hats

Now that we have gotten an overview of the history of witchcraft in medieval Europe, let us look at modern interpretations of witches and their medieval origins. Often today, witches are depicted wearing pointed hats with wide, flat brims. The exact origin of this is heavily debated. There are a few theories with origins coming from the medieval period through to the 17th century. We will focus on the possible medieval origins. One possible interpretation is the connections mentioned earlier between Jews and magic. In 1215, the Fourth Council of the Lateran made an edict that forced Jews to wear a particular hat, called Judenhut in German, to distinguish them in society. This hat as you might have guess was a cone-shaped, pointed hat. This antisemitic explanation is one possible origin.

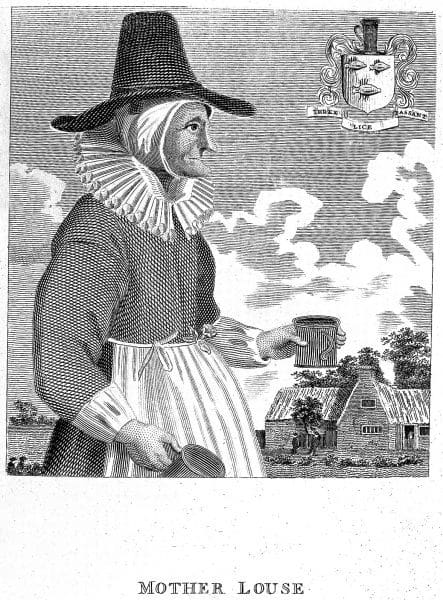

Another possible option is the idea of it being an association with a brewster’s, or ale-wife’s hat. An ale-wife was a woman who kept an ale house or sold ale. Selling ale was one of the few lucrative and stable careers available to most women at the time. They would wear a conical hat to indicate their profession. Their work with herbs and alcohol is the basis of this origin story. For a more in-depth exploration of the origins of the witch’s hat, including its 17th century connections, you should check out dress historian Abby Cox’s YouTube video on the topic.

Wands

Wands are easily the other most recognizable symbol of magic and witchcraft. While the idea of wands is quite old, its introduction into the world of magic stems from the Book of Honorius. The Key of Solomon repeated the idea of wands. 19th century translations of the Key of Solomon would popularize the concept of a wand being a tool for witches. This became especially true with modern pagan and Wiccan practices.

In Summary

While this is not an exhaustive explanation of the history magic and witchcraft in medieval Europe, we hope that this article gives you a better understanding of the topic. From widespread acceptance to widespread condemnation and persecution, the attitudes of Europeans changed greatly regarding magic over the centuries. Their opinions and ideas about magic still influence today’s views on the topic. If you are interested in fictional witches and wizards, be sure to check out our article on the topic.