A Brief History of Joan of Arc

Leaving her village: Domremy, located in northeastern France

Joan, daughter of Jacque and Isabelle d’Arc, was born in 1412 in the village of Domremy, located in northeastern France. At the start of the Hundred Years’ War, Henry V of England smashed the flower of French chivalry at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415 and made subsequent conquests throughout northern France. Northeastern France was controlled by England and their French allies: the Burgundians, Frenchmen who were under the leadership of the current Duke of Burgundy: John the Fearless. In 1420, King Charles VI of France signed the Treaty of Troyes, declaring Henry and his heirs the rightful heirs to the French crown. Remember dear reader, you’ll know you’re reading English history if it’s a history of Edwards and Henrys. If it’s French history, it’ll be a history of Charles and Philips.

Charles VI of France would be known to history as “Charles the Mad,” prone to fits of mental instability during his reign. His brother Louis, Duke of Orleans, clashed with their cousin John the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy, over the regency. Louis was assassinated by the Burgundians in 1407, kicking off the civil war between the Burgundians and the allies of the Count of Armagnac, who were fostering Louis’ son Charles. This is where they get the name “Armagnacs” for their faction. John the Fearless was assassinated later in 1419, and he was succeeded by his son Philip III.

Charles VII, son of Charles VI, became heir after a long and complicated struggle for the position of heir apparent to the French throne. Henry V was a skilled warrior and a powerful king, but he unexpectedly died of dysentery in 1422, and his infant son Henry VI was too young to inherit the throne of France and England at the same time. Charles VII, last surviving son of Charles the Mad, was declared the Dauphin, the position of heir apparent to the French crown by his allies in the Armagnacs.

Domremy was, at this time, one Armagnac village surrounded by pro-Burgundian territories. By 1425, at the age of thirteen, Joan likely witnessed raids on her home and heard about the devastation the civil war had brought. Joan was an unexpectedly pious child, always eager to go to Mass and practice her faith diligently. Joan claimed to have heard voices at an early age, and the exact origins for these voices are debated extensively. It’s possible that she was affected by bovine tuberculosis from drinking raw, unpasteurized milk or an acute form of epilepsy triggered by auditory cues like ringing church bells. Wherever the voices came from, they were supposedly the voices of God, angels, and various saints. Saint Michael, Catherine, and Margaret were described as chief amongst them. They told her to help “the King of France” reclaim his realm from the English and the Burgundians. She was given her mission and made all haste to fulfill it.

Meeting Charles VII at Chinon

She was given a horse, men’s clothing, and a sword to protect her on her journey. The men’s clothing given to her was special, tied together in such a way that made it difficult to take off if she was assaulted. After leaving her home of Domremy, she appeared at the Royal Court of the Armagnacs in the fortified town of Chinon. Enter: Charles VII, recognized as the rightful Dauphin of France by the Armagnacs and the old guard loyal to the Valois. Chinon was the base of operations for Charles VII and his Armagnac allies. Its strategic location placed him closer to the frontlines of battlefields like Orleans, the next city under attack by the Anglo-Burgundians in 1428. Joan arrived at a court dismayed but not defeated. Hope, and time, were running out for the Dauphin. Then, suddenly, this teenage girl claimed she had heard the voice of God. She said she had come to assist the Dauphin in driving the English out of France for good.

According to the accounts, the Dauphin and Joan had two private conversations. After the first, the Dauphin and the Armagnacs wanted to be sure that Joan was, in fact, sent to them by God. Was this girl holy, or was she a pawn of Satan sent to infiltrate and destroy the Armagnacs? She was sent to Tours and examined by French Catholic nuns who affirmed her virginity. Then, she was sent to Poitiers to be examined by French theologians to confirm her piety. After both came out positive, her divine mission was accepted as genuine, and Charles could breathe a sigh of relief. For added context, medieval Europeans were deeply spiritual and very superstitious when it came to angelic possessions and divine visions. Joan was certainly not the first, nor the last, person in medieval France to claim she was chosen by God. It’s important to remember in medieval European politics that God was an active force who communicated His will through signs and omens in the lives of everyday people.

For Charles and his allies, the smartest choice was to send her to Orleans. There was a relief force heading there anyway, so if she tagged along and broke the siege, great. This would mean she was truly ordained by God to help their cause. If she lost, then that would be telling, too.

The Siege of Orleans

Shortly before she left, she was gifted with a white harness, a phrase describing an unadorned suit of armour. (Harness comes from a French word meaning “armour.”) This armour was commissioned by Charles VII, a handmade suit of plate designed to fit her to exacting standards for battle. At this time, medieval armour was either: handcrafted by commission to fit an individual knight, noble, or monarch, or mass-produced to fit large feudal armies within a military-grade standard. Joan’s armour was specifically designed for her, allowing her as much protection while limiting her movement as little as possible.

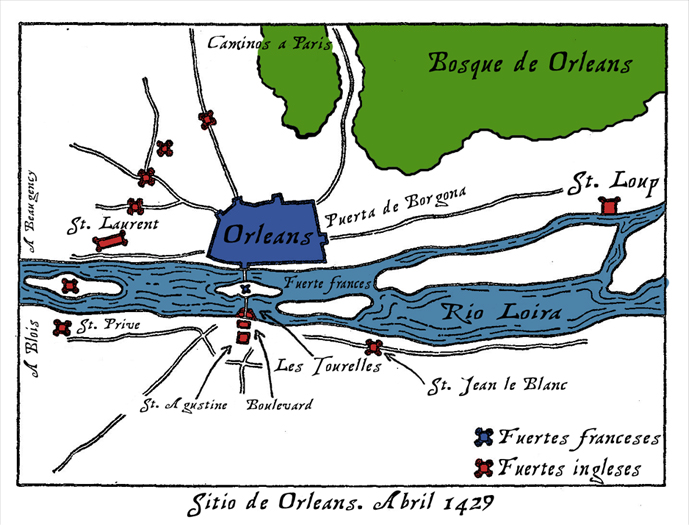

Here’s a closer look at how the situation of Orleans was going: bad. The English and Burgundians had surrounded the city with fortifications and there was a narrow bridge named Les Tourelles leading out of the city to the Les Augustins gatehouse. The only problem? That gatehouse was firmly in English control. In late April to early May 1429, Joan had proved to be a great choice for not only relieving Orleans, but uplifting the morale of the beleaguered French troops, too. She entered the city after a sortie from the citizens of Orleans distracted the English long enough for her to slip through. The sortie, also known as a sally-out, is a strike made by defending troops coming out from their defenses before retreating to the castle or settlement. Perhaps this attack was planned, perhaps not. If it wasn’t planned, then Joan would have likely thought it another sign from God that she was on the right path. If it was planned, she likely would have thought it God’s plan, too.

Joan gained valuable battlefield experience over the coming days. She was always in the thick of the fighting whenever the Armagnacs went out to battle. Try to imagine this teenage girl, not even 18 years old yet, close to brutal, bloody medieval fighting when fully grown men armed to the teeth hacked, bashed, punched, stabbed, and killed each other on the battlefield. Remember folks, most battles between heavy infantry wearing plate armour always devolved into wrestling matches. Unlike what Hollywood tells you in movies, armour worked. Exploiting weak points in the armour or overwhelming the opponent’s defenses were two of the only assured ways of winning in hand-to-hand combat. Joan never actually fought nor killed anyone. Simply witnessing such close-quarters fighting would have been jarring for anyone, much less someone who, at their core, was still just a kid. Instead, she rode through the back lines urging the troops on with her white and gold banner flying high.

Nevertheless, the experience she gained as a battlefield commander proved useful. The Armagnac commanders preferred not to include her in their councils on account of her inexperience, but she proved useful and offered them good advice on several occasions. She learned about the importance of battlefield logistics, troop deployment, and the most important part of siege warfare in the high medieval period: artillery placement. That also means cannons. The final assault on Les Tourelles was her idea. The fortress of Les Augustins was captured on May 6th, and the remaining obstacle was Les Tourelles. While the Armagnac commanders debated on the next plan of attack, Joan said she already had a plan: attack!

Soon enough, Les Tourelles fell like all the others. Even after being shot with an arrow in the neck, Joan returned to the battle as the castle was being overrun by French knights and men-at-arms. This is where she earned the title: “The Maid of Orleans.” Such a victory was precisely what the Armagnacs needed to turn the war back in their favor.

The Loire Campaign

Joan, now known as the Maiden of Orleans, and La Pucelle, had just firmly established herself as a tested battlefield commander among the Armagnacs. Charles was now fully convinced of her divine mission. The next target was the Loire Valley, not just to push the English and the Burgundians out, but to let Charles and the rest of the Armagnac court in. The Dauphin, Joan said, must be crowned at the city of Reims, located northeast of Paris. The English-Burgundian army was no longer a threat after their defeat at Orleans. Mustering an army takes time. Once an army is defeated, it takes a long time to piece it back together or create a fresh one. Charles VII was crowned King of France in the Cathedral of Reims, much to the delight of the Armagnacs who had fought, bled, and died to protect his claim. God’s will, according to Joan, had been fulfilled. But the war was far from over.

To consolidate his power, Charles VII negotiated a fifteen-day truce with the Burgundians, giving both sides time to rest and recover from the fighting. This did not sit well with Joan. The aggressive, temperamental teenager wanted to bring the sword to all the enemies of France within her borders. Paris was the capital of France itself. It had to be in Armagnac hands before Joan’s time was done.

While she would never have admitted it, there was some doubt brewing in Joan herself. God’s will had been done. Charles VII was crowned King of France, and the Armagnacs were now firmly in power. So, her job was done, right? Not exactly. There were still Burgundians to the east and English to the north, and the country was far from stable. The seasons are turning at this point. September is right around the corner in 1429, and the pressure was on Joan to fulfill her divine mission before it was too late. Would it have been impossible for her to fulfill her mission during the winter? No, not exactly. But there’s good reasons to not wage war in the snow.

The Armagnacs had an army ten thousand strong, many of them filled with divine purpose after having fought beside Joan for several months in the Loire Campaign. Surely, the garrison of a mere three thousand would fall and Paris would be liberated in short order. On September 8th, 1429, the Armagnacs launched an assault on the Porte Saint-Honore. This was the primary gatehouse of Paris and the site where the defenders had to hold. If this gate fell, then Paris fell with it. Swords were drawn, arrows were nocked, banners flew, and the attack began. This is where Joan is wounded. Within the first couple hours of the fighting, a crossbow bolt punched through Joan’s thigh and her banner carrier was said to have been killed by crossbow bolts, too. This wasn’t the first time she was wounded, but this time it was different. Crossbow bolts are deadly even for steel-clad knights, much less small teenage girls. She survived, but it would take a long time for her to recover.

Four. Hours. Four hours of fighting drags by without any progress made on account of the attackers. Charles VII gave the order to retreat, and the Armagnacs suffered 1,500 battlefield casualties. This would have been devastating for any feudal army, much less the army of the King of France. After this disastrous defeat, members of his court began to doubt her, and she was increasingly shut out of correspondence within the Armagnac inner circle. There was simply no way for Joan to explain her defeat. During the truce that followed, she started receiving letters from all over Europe asking her for her opinion on contemporary matters. Several Popes were vying for control of the Catholic Church during this time, and people wanted to know which they should support. Even though, despite dictating letters written by scribes, Joan could barely write her own name.

The Siege of Compiegne and Joan’s Capture

In December, Charles ennobled her family in gratitude for her service. Though her family were now minor nobles of the realm, this was probably intended to be an “honorable discharge” so the King wouldn’t risk her stirring up more trouble in his court. The truce between Duke Philip III of Burgundy and King Charles VII extended well into Easter of 1430, during which time Joan was no longer needed. There were no battles to fight, and she was already slipping from the court’s favor. Many settlements outside Paris were given to the Duke in the treaty, but most were loyal to the Armagnacs. Compiegne was one of those settlements. Luckily for Joan, the war flared up again when Philip III reneged on the truce and led an army to occupy the towns given to him by the treaty.

Seizing the opportunity, Joan flung herself back into the war in late May by rallying several commanders to her banner and setting out to halt the army of Philip. All without the official support of the Armagnac court. At the head of the Burgundian force was a longtime ally of Philip: John of Luxembourg. Joan defeated a Burgundian garrison at Lagny-sur-Marne just outside Paris and captured one of the mercenaries in command: a man named Franquet of Arras. This mercenary was put on trial by the townspeople under the watch of Joan, and since she did not have any legal experience, she was mostly unconcerned with it. He was an enemy, a murderer, and a traitor, and as such Franquet of Arras’ trial was heavily skewed. Surrounded by Armagnac supporters and being tried before an Armagnac-leaning court, there was simply no chance of his survival. In medieval warfare, commanders, lords, and knights were usually ransomed as valuable prisoners of war. This practice kept money moving, where defeated lords could return home and try their luck again while their captors received a paycheck for their skills in battle. Men-at-arms, levy soldiers, and peasant militia, however, did not receive the same luxury.

Some accounts say the governor of Compiegne turned traitor and closed the gate before Joan’s rearguard could enter the city. Others claim it was practical. The governor likely saw how big the Burgundian force was and did not wish to risk them entering the city in pursuit of the retreating Armagnac force. Regardless of which is true, Joan’s rearguard was surrounded, and she was captured.

The Condemnation Trial

John of Luxembourg’s forces realized that capturing La Pucelle was a bigger prize than the whole city of Compiegne. Instead of being ransomed back to the French, Joan was kept in captivity while John made plans of his own. After months of captivity and several escape attempts, she was finally sold to the English. In February of 1431, the castle of Rouen was decided as the place for her trial. Joan’s entire life was used as evidence in what would be known as the Trial of Condemnation. Everything from her visions, her choice of wearing men’s clothing, leading men to war, and her piety were put under intense questioning. This was a trial the English and the Burgundians could not afford to lose.

Arguably, the most famous example of her rhetoric and sharp intelligence comes from an exchange between her and Pierre Cauchon. Cauchon was an Anglo-Burgundian supporter and the Bishop of Beauvais, serving as the primary judge of Joan’s trial. She was asked whether she believed she was in God’s grace. She might not have known it at the time, but it was a scholarly trap devised by the inquisitors referring to church doctrine. No one could know whether they were in grace, and affirming so would be considered heresy. If she claimed she was not, then this would be a confession of her guilt.

In a master stroke, she defused the trap by stating: “If I am not, may God place me there; if I am, may God so keep me. I should be the saddest in all the world if I knew that I were not in the grace of God…” (From the Third Public Examination transcript). After several days of questioning, she was given a chance to confess her sins before the inquisitors in exchange for life imprisonment. She eventually confessed, likely out of fear for her soul. The court made her sign a document stating she would change her ways and stop wearing men’s clothing. According to the document, she would return to wearing women’s clothing and be forgiven for her sins. Often, the church welcomed repentant sinners who confessed and agreed to change their ways.

However, there was a complication. After a short while, she returned to wearing men’s clothes while in captivity. There are a few perspectives on this event. Either she was assaulted by her guards and forced to wear male clothing again, or she willingly put them back on to deter said assault. The judges and inquisitors of the court declared her a “relapsed heretic,” and decreed that she be burnt at the stake. On May 30th, 1431, she was sent to the stake in the marketplace of Rouen.

One soldier out of the crowd, likely one who had been on the opposing side, lifted a cross so that she may look on it as she burned alive. So ends the story of Joan of Arc. Though, it was not the end of her legacy, far from it. Even though the girl savior of France was burned and her ashes thrown in the river, the fighting spirit of the Armagnacs did not dampen. For the next twenty years, the English were pushed back, and the Burgundians eventually ended their alliance them, allowing Charles VII to claim Paris. In 1449, the fortress of Rouen fell to Charles VII, known to history as: “Charles the Victorious.” Apart from Calais, the English no longer controlled any territory in France.

Centuries after her death, the Church would canonize Joan of Arc as a saint in 1920, rectifying her guilt and declaring her a heroine of France. Her legacy endures in Domremy, Reims, Chinon, and Rouen to this day. Festivals are still held in her honor at Orleans.

What did we learn while making the Fantasy Joan of Arc Womens Outfit?

One of the most important topics we learn about and discuss here at Medieval Collectibles is the practice of “donning” and “doffing” armour. We’ve had our fair share of harnesses, kits, and suits of armour in the past, but each case is different and comes with their own unique set of challenges. Challenges such as the body type and overall size of the person wearing the armour, the availability of the armour pieces, size of the armour, clothing and accessories, and most importantly: why the armour is worn in the first place.

The Fantasy Joan of Arc Women’s Outfit (OUTFIT-F122) blends the elegance and purity of Joan’s character with the martial presence of fully armoured knights fighting in the Hundred Years’ War. We wanted to build an outfit that lets you step into the age of swords, castles, and chivalry without weighing you down with a complete suit of armour. As such, the bundle gives you a lovely white undertunic and skirt as a great base layer for the armour and mail. It’s also highly recommended to wear arming wear beneath armour, as the extra padding can add protection and comfort on your adventures. The armour pieces in the bundle are designed to fit you as best as possible. No two heroines are the same, and our Joan of Arc outfit has different sized armour for the best fit.

There were quite a few things we learned from Jeanne d’Arc. Not only does she open valuable conversations about medieval perceptions of neurology, women in war, and medieval belief, but she also fits into an iconic underdog archetype in medieval history. Thanks to the transcripts preserved in her trial, she is more documented than most kings and queens for her time. Studying her life allowed us to gain new insights into the medieval period and bring that to life with our arms and armour. If you’re as passionate about medieval history as we are, be sure to check out all kinds of weapons, armour, clothing, and accessories to help bring your historical characters to life.

Sources

Barrett, W.P. “The Trial of Jeanne D’Arc – Translated into English from the original Latin and French Documents. WITH AN ESSAY On the Trial of Jeanne d’Arc AND Dramatis Personae, BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES OF THE TRIAL JUDGES AND OTHER PERSONS INVOLVED IN THE MAID’S CAREER, TRIAL AND DEATH BY PIERRE CHAMPION.” Translated by Coley Taylor and Ruth H. Kerr. Internet Medieval Sourcebook, September, 1999. https://web.archive.org/web/20160818165959/https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/basis/joanofarc-trial.asp

Bie, Soren. “Banner: Joan of Arc.” Joan of Arc – (1412 – 1431), April 11, 2025. https://www.jeanne-darc.info/biography/banner/.

Bie, Soren. “Suit of Armour: Joan of Arc.” Joan of Arc – (1412 – 1431), April 11, 2025. https://www.jeanne-darc.info/biography/suit-of-armour/.

Bie, Soren. “The chronicles of Enguerrand de Monstrelet – From Enguerrand de Monstrelet, Chronicles of Enguerrand de Monstrelet, trans. Thomas Johnes, vol. 1 (London: Henry G. Bohn, 1853).” Originally prepared by Leah Shopkow. Associate Professor History Department, Indiana University. Joan of Arc – (1412 – 1431), November 14, 2024. https://www.jeanne-darc.info/contemporary-chronicles-other-testimonies/the-chronicles-of-enguerrand-de-monstrelet/.

Bie, Soren. “Trial of Condemnation 1431: Joan of Arc.” Joan of Arc – (1412 – 1431), November 14, 2024. https://www.jeanne-darc.info/trial-of-condemnation-index/.

Brehal, Jean. “Jean Brehal, Grand Inquisiteur de France, et la Rehabilitation of Jeanne D’Arc.” Belon, Marie-Joseph, Balme, Francois (University of Wisconsin) 1893. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/jean-brehal-grand-inquisiteur-de-france/page/n213/mode/2up

Breiding, Dirk H. “Arms and Armor – Common Misconceptions and Frequently Asked Questions.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 1, 2004. https://www.metmuseum.org/essays/arms-and-armor-common-misconceptions-and-frequently-asked-questions

Chastellain, Georges. History of Charles the bold, Duke of Burgundy vol. 2. Translated by J.B. Lippincott & Co, (Cornell University Library), 1864.

Curry, Anne, ed. The Hundred Years War Revisited. Problems in Focus. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019. Accessed June 22, 2025. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350494664.

Curry, Anne, The Hundred Years War. St. Martin’s Press, 1993.

DeVries, Kelly. Joan of Arc: A Military Leader. Gloucestershire, England: Sutton Publishing Ltd., 1999. https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780750918053/page/n279/mode/2up

Gaillard, Philippe. Joan of Arc’s Army: French armies under Charles VII, 1415–53. Osprey Publishing, 2024.

Nicolle, David. French Armies of the Hundred Years War. Illustrated by Angus McBride. Osprey Publishing, 2000.

Pizan, Christine. “Christine de Pizan: Joan of Arc.” Joan of Arc – (1412 – 1431), November 14, 2024. https://www.jeanne-darc.info/contemporary-chronicles-other-testimonies/christine-de-pizan-le-ditie-de-jehanne-darc/.

Raitt, Jill. “Joan of Arc, Her Story. By Régine Pernoud and Marie-Véronique Clin.Revised and Translated by Jeremy duQuesnay Adams. Edited by Bonnie Wheeler. New York: St. Martin’s, 1998. Xiv + 304 Pp. $27.95 Cloth.” Church History 68, no. 4 (1999): 989–91. https://doi.org/10.2307/3170232.

Schildkrout, Barbara. Joan of Arc–Hearing Voices. American Journal of Psychiatry, AJP, 174, no. 12 (December 2017): 1153–54. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17080948.